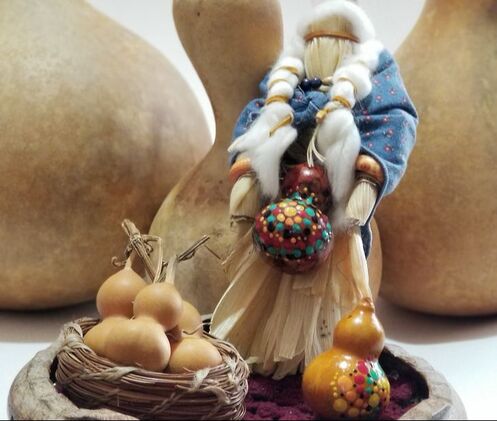

Cohanzick Lenape No-Face Doll Art

This art is a long tradition among the Lenape. Whenever we create our likeness of any living creature, past or present, we never put a face on it. We do not believe it is our place to make any likeness of any face or creature. Only the creator has the privilege of doing so.

The "No Face Ancestor" art helps me keep this tradition alive. However, it also provides me a unique opportunity to explore my artistic ideas about translating its message into my artwork. I create something different without losing its importance to me, my people, and everyone who communicates with it. There are many ways to create no-face dolls.

I have practiced this art from the age of seven. I first learned about cornhusks, rag dolls, gourds, and leather. Today I continue to use the cornhusk, leather, and gourds to create my art.

The "No Face Ancestor" art helps me keep this tradition alive. However, it also provides me a unique opportunity to explore my artistic ideas about translating its message into my artwork. I create something different without losing its importance to me, my people, and everyone who communicates with it. There are many ways to create no-face dolls.

I have practiced this art from the age of seven. I first learned about cornhusks, rag dolls, gourds, and leather. Today I continue to use the cornhusk, leather, and gourds to create my art.

No-Face Doll Video

Close-up video of the sewing process of the no-face doll body

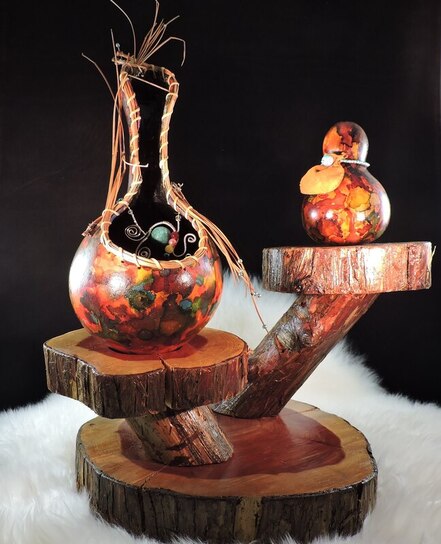

Cohanzick Lenape Gourd Art

Considering all that I create, I think my "No Face Ancestor," Lenape Gourd Art, may be the dearest to me. This gourd art is a creation from my heart that was inspired after many years of meditation. Gourds take many years before they can be created into another form, from when I hold the seed in my hand and place it in the fertile soil as I watch it grow and take shape. Sometimes, I stare at the form that it takes, and it speaks to me and tells me what it should be. The gourd's seed carries my ancestors; it brings the past, then it continues to give life; it provides beauty; it is a gift.

Each seed has the mark of its ancestor, and each gourd influences the past. I think of my ancestors as I plant the seed in this fertile soil, and I give thanks that I can be a part of a long creation process. Sometimes, I hold the gourd in my hands for many hours before it speaks to me and describes what it should be. Sometimes, I can turn it into a vessel or a rattle, but other times when I hold the gourds, they inspire me to become a Lenape "No Face Ancestor." This art is a long tradition among the Lenape.

Each seed has the mark of its ancestor, and each gourd influences the past. I think of my ancestors as I plant the seed in this fertile soil, and I give thanks that I can be a part of a long creation process. Sometimes, I hold the gourd in my hands for many hours before it speaks to me and describes what it should be. Sometimes, I can turn it into a vessel or a rattle, but other times when I hold the gourds, they inspire me to become a Lenape "No Face Ancestor." This art is a long tradition among the Lenape.

Gourd Video

Video showing how I clean and cut the gourd the natural way to prepare for the no-face doll.

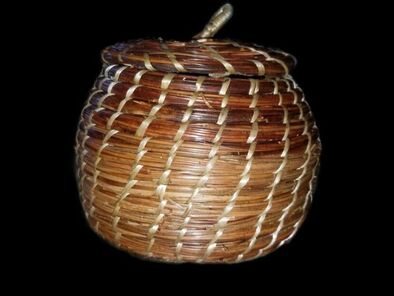

Cohanzick Lenape Pine Needle Art

This is one of my oldest art forms practiced. I feel as though I can take what the tree has given and has let go after it shades and houses the birds and other animals' lives. My creations of Lenape "Infinity Spiral" Pine Needle are from the long needles that fall to the ground to create baskets, hairpieces, and ornament my regalia as a work of art. It is such a simple process, and yet, it creates a beautiful spiral that can be inspired to take many forms and uses. The trees carry my ancestors through their leaves. The tree is a gift that is continuous from our past. The Lenape "Infinity Spiral" Pine Needle Art is a reminder that we continue to grow and expand and are a part of history and contribute to the future.

Pine Needle Video

Video of the pine needle basket making

Other Cohanzick Lenape Art

As an artist, I like to create using many forms of materials. Below are a few samples of my other art.